Meeting Youth Mental Health Needs

School is underway for K-12 students, variants of COVID-19 continue, and many students still face mental health challenges brought on by or increased due to the pandemic. Following the U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Children’s Mental Health, Children’s Advocates for Change (CAFC) undertook a closer look at the subject this summer. We talked to state and national experts, school social workers, and students. In our latest policy paper, CAFC outlines the data, state programs underway, and further steps the state of Illinois can take to best meet the mental health needs of our youth.

At Home and Isolated

In the early part of the pandemic, schools shutdown in-person learning and switched to remote learning via computers. School is generally where students meet their friends, and when school closed, so did many of their doors to socialization, social development, and ability to interact outside of a screen, leading to a significant increase in isolation. The physical isolation, combined with job losses by parents and caregivers, illnesses, and deaths brought about increased levels of anxiety and depression for many young people. All of this came on top of other factors impacting youth mental health that include poverty, violence, and negative social media messages.

Two self-report surveys help capture the state of youth both during the pandemic and the time leading up to it. A January–June 2021 survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of 7,705 public and private high school students showed 37.1% of responding high school students experienced poor mental health most of the time or always during the pandemic. More than 44% of the total respondents reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness.[1]

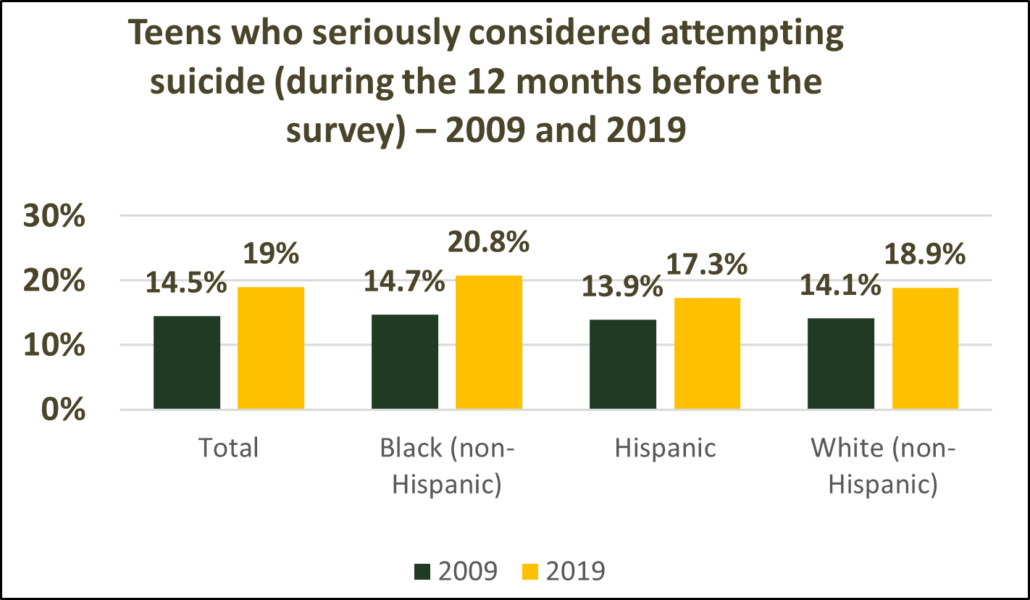

The CDC also conducts a national survey, and state departments of health and education conduct statewide surveys, that feed into the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) which helps monitor health behaviors and social problems among youth.[2] Asked in 2009 if a student felt sad or hopeless for two or more weeks in the year before the survey, 27.8% of Illinois students surveyed said “yes”. Ten years later 36.3% said “yes”….an increase of more than 30%. Data reflecting whether a student seriously considered attempting suicide also increased.[3]

What School Social Workers Saw

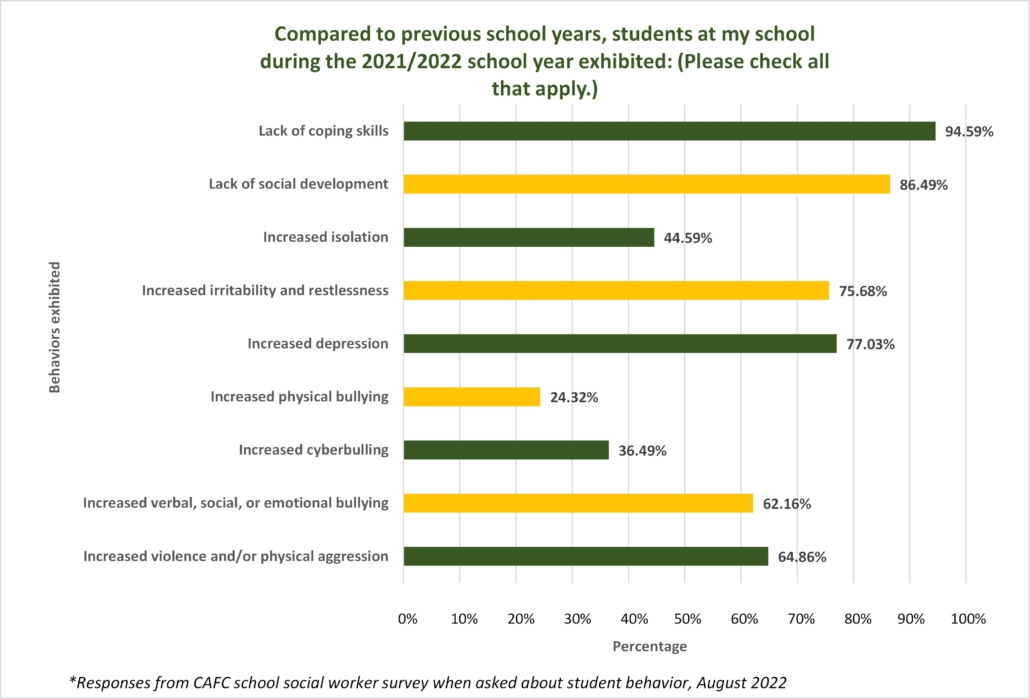

Children’s Advocates for Change surveyed 76 school social workers from around the state of Illinois regarding student mental health at their school. This was a self-reported survey in August of 2022 gathering the perspectives of school social workers about students from various grade levels, some as young as pre-kindergarten, all the way through high school.

- Over 86% of respondents agreed that student mental health was currently a concern at their school.

- Over three-quarters of school social workers stated there were not enough resources to meet the needs of the students in their school.

- An overwhelming response of almost 82% of school social workers indicated there were barriers to the ability for students to receive mental health services at their school.

The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) recommends schools maintain a ratio of one school social worker for 250 students (.004). Under Illinois law (105 ILCS 5/34-18.58) the state recommends the noted NASW standard but does not require the ratio be maintained.

A February 2022 report by the entity Inseparable put the Illinois social worker to student ratio at one to 741 students and the ratio of counselors to students at one to 626. [4]

Telehealth

Our policy paper also looks at school use of telehealth to deliver mental health services to youth. While it holds promise for addressing access issues in urban and rural areas, issues remain with inequities in access to broadband services and needed electronic devises such as laptops, desktop computers, tablets, and cell phones.

Poverty, trauma and inequities

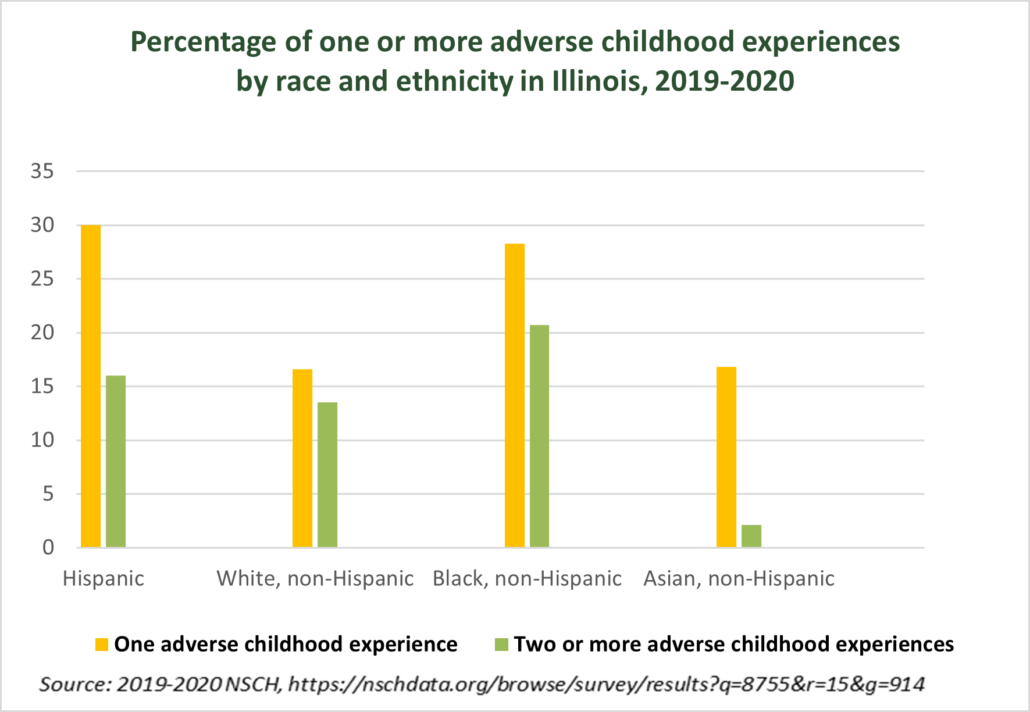

Poverty, education, neighborhood violence, and other factors affect the likelihood of a youth’s exposure to an adverse childhood experience (ACE), and ACEs have a significant impact on youth developing mental health conditions.[5] In many cases poverty may be the main driver, impacting housing stability, food sufficiency, and the safety of a neighborhood in which a family resides.

While business shutdowns and slowdowns increased the economic needs in many households, particularly Black, Hispanic, and Latino households, economic inequalities existed before the pandemic. For example, U.S. Census Bureau numbers show the percentage of Illinois Black children in poverty versus white non-Hispanic children was more than three and a half times higher in 2019 (pre-pandemic).

The data on children exposed to adverse childhood experiences show differences by race and ethnicity – particularly with regards to exposure to one adverse childhood experience.

What Students Are Saying

Children’s Advocates for Change also spoke to more than 75 young people across the state from Chicago, the Chicago suburbs, East St. Louis, and Moline to hear from them what issues are impacting their communities. When we spoke with them about the issues affecting youth mental health, racism and homophobia were two of the top issues they felt were problems within the schools. Youth have expressed that it often feels as if there is not adequate intervention from the administration regarding reported concerns about these issues.

Delivering mental health services in a school setting can improve access to such care for many students. In poorer communities, whether it is due to insurance coverage, proximity of a community provider, use of a primary care physician versus a specialist, or a stigma families feel about mental health treatment, youth may not receive needed mental health treatment outside of school.

In our conversations with students about available mental health resources in school and whether it was easy to access help, one common theme that came up was that students felt there was an initial barrier to being able to leave the classroom. Another frequent topic was parents not understanding or invalidating the kids’ mental health challenges.

“Many people find it hard to access the help because they have to go out of their way just to ask/receive it and when they do, they only get it on certain days.”

Chicago Student

What Is Being Done

With pandemic relief legislation in 2020 and 2021, Congress approved approximately $190 billion for state education departments and local school systems to deal with COVID-19 related issues including learning loss, mental health needs, health protocols, and related modifications to buildings for health and safety improvements.[6]

Most of the federal COVID-19 relief money used for student mental health services came through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER). From ESSER federal funding, Illinois received a total $7.54 billion. Of that amount it kept, $476 million for state-directed programming with the remaining funds allocated to local school districts across the state.[7]

Some of the state efforts underway include Project Reach and Project AWARE:

Project REACH

In 2020, the Illinois State Board of Education established a partnership with the Center for Childhood Resilience (CCR) at Lurie Children’s Hospital to offer training and support to staff at seven social emotional learning hubs established across the state. Staff at these hubs then work with local school districts in training on student trauma evaluations, trauma-informed responses, and development of action plans to address issues identified in the evaluations.

Project AWARE

In 2020, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services launched Project AWARE (Advancing Wellness and Resiliency in Education), which made funding available through federal grants up to $1.8 million per proposed budget to support youth mental health needs in schools and in the community.[8] Currently, the only three Illinois school districts are participating: Chicago School District #299, Eldorado CUSD #4, and Bloomington School District #87.[9]

In addition to the federal pandemic relief funding provided to schools, recently approved federal gun safety legislation provides the potential of even more funding for the state to address student mental health needs. The bill contains the following funding sources:[10]

- $80 million for a pediatric mental health care access program, which allows pediatricians to provide mental health services via telehealth.

- $60 million over four years for training primary care clinicians to provide mental health services to young people.

- $250 million to increase the Community Mental Health Services block grants to states to help fill in blanks in a state’s mental health system.

- $240 million over four years to be added to Project AWARE, which provides grants to mental and behavioral health organizations, community groups, and schools to raise students’ awareness of and connect them to mental health services in schools.

- $150 million for the new 988 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

Recommendations for the state of Illinois

After examining not just Illinois’ efforts to address youth mental health needs but also efforts underway in other states, CAFC recommends Illinois legislators consider undertaking the following measures:

Conduct regular mental health assessments for students and use the data to establish grant programs for school districts:

Require Illinois schools to conduct a mental health and wellness assessment of students at least once per school year to determine needs for student population within each school district in Illinois.

Mandate school mental health staff to student ratios

As noted earlier, state law currently suggests but does not mandate a ratio of one school social worker for every 250 students for Illinois schools. This is not sufficient to address the youth mental health needs present in schools. CAFC recommends the state establish an appropriate ratio of school mental health personnel per student based on need as determined by the mental health assessment discussed above. Some schools may need a higher ratio (one social worker per fewer than 250 students). Additionally, the ratio, once established, needs to remain as a requirement to ensure students have access to the necessary resources.

Establish and expand school-based health resources with additional staff and telehealth

School-based mental health care is a positive solution to addressing youth mental health care by bringing the services to students. Increasing mental health staff (social workers, therapists, psychologists, and other behavioral health professionals) within the schools is critical to addressing youth mental health needs. While it should not be considered a long-term substitute for full-time social workers and counselors in school, telehealth does represent a means for a school to increase access to mental health treatment for youth in the short-term and it can then serve as a complement to in-person counseling.

However, increasing telehealth services needs to occur in conjunction with the state taking further action to increase the availability of broadband service (both in urban and rural areas) and ensuring students have access to a laptop, desktop computer, tablet, and/or smart phone to adequately utilize telehealth services.

Adopt a state child income tax credit

Illinois low- and moderate-income families could benefit from a state child tax credit to help them address economic needs that include housing, food security, and/or clothing and help mitigate the negative influence of poverty in a child’s mental health.

Enhance required mental health literacy training and/or mental health first aid programs for educators and parents through Illinois school districts

While it is important for school personnel, it is equally important for parents to have access to similar resources. Often, parents are not aware of the signs and symptoms of a mental health issue.

Related to our recommendations are continuing efforts to address the social determinants of mental health that include addressing food deserts, lack of affordable housing in some communities and regions of the state, and lack of access (or difficulty in access) to medical care providers.

On September 14, 2022, Children’s Advocates for Change held an online public policy forum on meeting the mental health needs of our youth. You can view the video on our YouTube Channel that includes a panel discussion on many of the issues noted here as well as portions of interviews from youth themselves.

Written by Sarah Stolarski-Galla and Mitch Lifson

____________________________________________________

Endnotes

[1] Jones SE, Ethier KA, Hertz M, et al. Mental Health, Suicidality, and Connectedness Among High School Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic — Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Suppl 2022;71(Suppl-3):16–21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3external icon.

[2] https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (n.d.-b). Disparities in mental health and suicide indicators among U.S. high school students, 2009-2019. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/mental-health-data-table.pdf

[4] Inseparable, America’s School Mental Health Report Card, February 2022. (Referenced data from the U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection [2015-2016] and the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics [2018-2019].) https://hopefulfutures.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Final_Master_021522.pdf

[5] Colizzi, M., Lasalvia, A. & Ruggeri, M. (2020). Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: Is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care? International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14(23). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00356-9

[6] Lieberman, Mark, and Andrew Ujifusa, “Everything You Need to Know About Schools and COVID Relief Funds”, Education Week, September 10, 2021, https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/everything-you-need-to-know-about-schools-and-covid-relief-funds/2021/09

[7] Information provided by the Illinois State Board of Education

[8] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. (2020). FY2020 Project AWARE (advancing wellness and resiliency in education) state education agency grants. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/grants/pdf/fy-2020-aware-foa.pdf

[9] Illinois State Board of Education. (n.d.). Illinois AWARE. https://www.isbe.net/Documents/SWC21-IL-AWARE-ppt.pdf

[10] Knight, Victoria, Gun Safety ‘Wrapped in a Mental Health Bill”: A Look at Health Provisions in the New Law, Kaiser Health News, July 7, 2022, https://khn.org/news/article/gun-violence-mental-health-legislation-suicide/