The Case for a State Child Tax Credit

History of the Federal Child Tax Credit

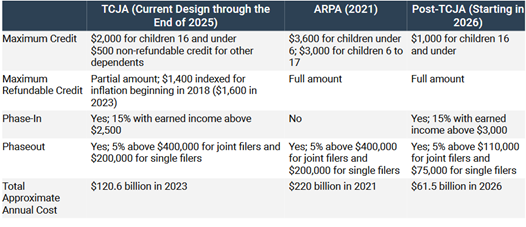

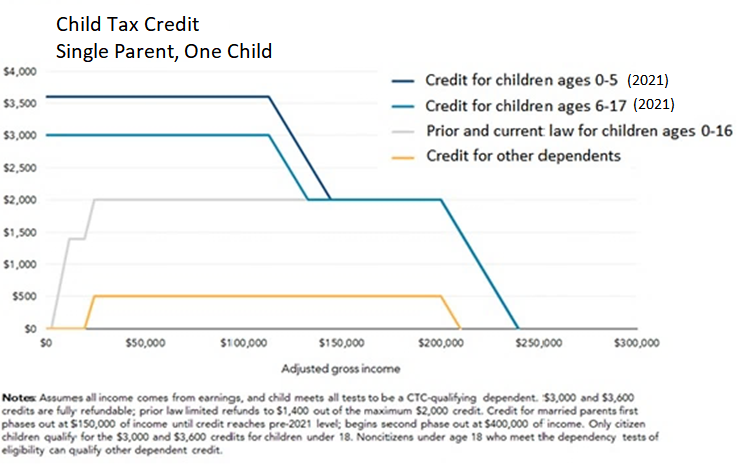

While first established in 1997, the federal child tax credit in 2016 had a maximum value of $1,000 for children 16 and under. An individual had to earn more than $3,000 and the credit value phased into the maximum value. The credit was fully refundable, meaning if the value of the credit exceeded a taxpayer’s tax liability then the taxpayer could receive a refund for the difference.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, increased the Child Tax Credit in 2018 to $2,000. The phase-in started at $2,500 and the credit refund was capped at $1,400 (an amount indexed to inflation that is worth $1,600 in 2023). Those changes now are in effect through 2025, when the tax parameters revert to the pre- TCJA guidelines.

In 2021, during the height of the pandemic, the federal government expanded the federal Child Tax Credit for but only one year. The maximum credit amount increased from $2,000 to $3,600 per child under age 6 and to $3,000 per child between the ages of 6 and 17. The federal government also made the credit fully refundable to low-income households. There was no income threshold to begin receiving the credit.

Source: Tax Foundation

Source: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center

Impact of the Child Tax Credit on Poverty

The 2021 enhanced federal Child Tax Credit, along with other economic supports, had a tremendous impact in lifting children out of poverty. Nationally, the supplemental child poverty rate dropped from 12.6% in 2019 to 5.2% in 2021. (Unlike the official poverty rate calculated by the Census Bureau, the supplemental poverty rate takes into account certain government benefits -such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, WIC [Women, Infants and Children] benefits, the Earned Income Tax Credit [EITC], the Child Tax Credit [CTC], and housing subsidies – as well as household expenses that include childcare costs, taxes, work expenses, and medical expenses[i].)

In Illinois, the supplemental poverty measurement rate from the census bureau went from 12.7% in 2019 for children under age 18 to 5.5% in 2021 (a reduction of 56.7%)[ii]. In 2022, because of the changes in the Child Tax Credit provisions (reinstating minimum income, capping the refund amount), an estimated 664,000 Illinois children under the age of 17 became ineligible for the full credit. The number includes 217,000 Latinx children, 199,000 white children and 198,000 Black children[iii].

| Number (in thousands) and Percentage of Children in SPM Poverty | ||||||

| Under age 18 | ||||||

| Number | Percent | |||||

| Estimate | M.O.E. (+/-)1 | Estimate | M.O.E. (+/-)1 | |||

| 2021 | Illinois | 152 | 15 | 5.5 | 0.5 | |

| 2019 | Illinois | 357 | 18 | 12.7 | 0.7 | |

| 2017 | Illinois | 427 | 18 | 14.8 | 0.6 | |

| Data are based on a sample and are subject to sampling variability. | ||||||

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2009 through 2019 and 2021 American Community Survey Public Use 1-year estimates. | ||||||

Exactly how many children who were lifted out of poverty in 2021 but now live in poverty is unclear. The Census Bureau will release 2022 statistics later this fall. The 2019 supplemental poverty measurement of children in poverty (an estimated 357,000) gives some indication. However, impacting that number are variations in job and wage growth both at the height of the pandemic and at the end of last year.

Without accounting for the additional revenue and expenditure measurements in the supplemental poverty measurement, the Bureau’s official poverty measurement shows the following for those in poverty and those in deep poverty (or 50% of the Federal Poverty Level):

| Children under the age of 18 | ||||||

| 2021 | 2019 | 2017 | ||||

| Illinois children in poverty | Below 50% FPL | 213,584 | 175,016 | 215,972 | ||

| Illinois children in deep poverty | Below 100% FPL | 442,261 | 436,327 | 486,196 | ||

| Percentage of Illinois children in poverty | 16.0% | 15.7% | 17.0% | |||

| Numbers reflect those for whom the poverty status is determined. | ||||||

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 1-year data | ||||||

Household Needs and State Activity

It’s very likely that with a minimum income level reinstated, those in deep poverty will be most impacted by the federal Child Tax Credit changes. While inflation has decreased from the recent peak of 9.1% in June (year-to-year), food prices and rents still remain high. Data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (covering July 26-August 7, 2023) shows of all Illinois households with children answering the survey 12.9% either often or sometimes did not have enough to eat in the last seven days. That value rose to 38.2% for Black households with children and 19.6% for Latinx households with children. Even in households receiving assistance under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program the number stood at 25.4%[iv].

The Greater Chicago Food Depository reports (based on data collected by Northwestern University) that 23% of Chicago metro area households with children were food insecure from March-April 2023[v]. The Depository also reports that of its network of more than 800 partner pantries and meal program sites across Cook County served 31% more guests in May of 2023 than the same month last year.

A previous blog post noted not only the racial disparities in poverty (and the fact that poverty for Latinx and Black children grew from 2019 to 2021) but also the fact that most two-adult/two-child households need closer to 3 times the official poverty level to meet household expenses and attain a modest standard of living.

The noted reduction in child poverty with the enhanced federal Child Tax Credit combined with the failure of Congress to continue that enhancement beyond one year calls for the need for a state Child Tax C\credit to help reduce child poverty. Utah, Oregon, and Minnesota adopted state Child Tax Credits this year and join 11 other states. In all except four states the credit will be refundable for 2023 tax year. (In addition, Arizona adopted a one-time child tax rebate.) Minnesota Governor Tim Walz predicts the state’s new Child Tax Credit will cut child poverty in Minnesota by one-third[vi].

It is more than just the short-term economic infusion of cash.

![]() Child Welfare Prevention

Child Welfare Prevention

Research shows social determinates of health (including poverty, housing instability, and food insecurity are associated with child maltreatment[vii]. Additional research documents that with increasing county child poverty rates, total and type-specific official maltreatment rates increased in all race/ethnicity groups[viii].

Increased economic supports are associated with a decreased risk for neglect and physical abuse[ix]. A study published of cross-sectional study of 3,169 emergency department visits related to child abuse or neglect found fewer child abuse and neglect-related visits in the four days following expanded Child Tax Credit payments in 2021[x]. Another study found the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and federal Child Tax Credit (CTC) are associated with a 5% reduction in child maltreatment reports in the four weeks following families’ receipt of the tax credit.

![]() Children’s Health

Children’s Health

Poverty, and associated factors such as inadequate nutrition, can negatively impact the development of a child’s body, including the brain. Children who directly or indirectly experience risk factors associated with poverty have higher odds of experiencing poor health problems as adults such as heart disease, hypertension, stroke, obesity, certain cancers, and even a shorter life expectancy[xi].

Research on the EITC (refundable on both the state and federal levels) shows increases in the credit have led to improvements in birth weight and lowered premature births[xii]. Contributing factors may be improved access to prenatal care and reduced maternal stress[xiii].

![]() Education

Education

According to the Urban Institute, persistently poor children (children poor at least half of the years from birth through age 17) are 13% less likely to complete high school by age 20 and 43% less likely to complete college by age 25 than other poor children[xiv]. Contributing to lower academic achievement is residential instability due to poverty.

Research suggests that an additional $1,000 in in the EITC for a household with children when a child is 13 to 18 years old increases the likelihood of completing high school by 1.3% and completing college by 4.2%[xv].

![]() Economic Benefits

Economic Benefits

The economic benefits from the ETIC or CTC accrue not just to recipients of the credits but state and local economies as well. For low-wealth households, the marginal propensity to consume (that is how much more a person spends when their income increases) is 10 times larger than it is for wealthy households[xvi]. A state will recoup part of the spending through sales taxes and the economic activity may generate more jobs. One Congressional report estimates that the expanded federal CTC created significant benefits for local economies with $1.25 generated for each $1 in CTC payments[xvii]. A working paper issued by National Bureau of Economic Research estimates that for households earning less than $50,000 for each $100 increase in CTC payments those households spend $85 with the top categories housing ($33.18), food ($29.50), clothing ($7.87) and transportation ($7.67)[xviii].

Unlike programs where a benefit may only be used by a recipient for food, housing, or another specific purpose, a state child tax credit provides a family the flexibility to use the new financial resources in a way that best suits the household -whether it is for food, housing, child care, transportation, or clothing.

Time to Act

There are short and long-term benefits to the state by creating a state Child Tax Credit. There are the short-term benefits of addressing food insufficiency and housing instability as well as the noted economic activity around the state. With the potential of improved health, educational attainment, and even future earnings as children move to adulthood, the credit offers potential long-term savings for the state. In addition, given the Illinois’ flat income tax provision and the regressive nature of our state and local tax systems, a state child tax credit adds greater progressivity into the system.

The 2021 federal action to expand the Child Tax Credit showed how successful government can be in taking major steps to address child poverty when it decides to do so. Unfortunately, that effort lasted for only one year. Now the state needs to step in to build on that investment and give all children the opportunity to thrive.

Written by Mitch Lifson

[i] U.S. Census Bureau, Measuring America: How the U.S. Census Bureau Measures Poverty, June 2022

[ii] U.S. Census Bureau, Supplemental Poverty Estimate using American Community Survey Public Use Data.

[iii] Cox, Kris, Chuck Marr, Sarah Calame, and Stephanie Hingtgen, “Top Tax Priority: Expanding the Child Tax Credit in Upcoming Economic Legislation”, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 12, 2023.

[iv] U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Week 60

[v] Greater Chicago Food Depository , “Food for Thought”, Summer 2023

[vi] A maximum credit of $1,750 per child for households of $29,500 for single tax filers and $35,000 for joint tax filers. The credits begin to decrease after reaching those thresholds.

[vii] Hunter, Amy and Glen Flores, “Social determinants of health and child maltreatment: A systematic review”,

Pediatric Research, 89, 269–274, 2021.

[viii] Kim, Hyunil, and Brett Drake, “Child maltreatment risk as a function of poverty and race/ethnicity in the USA”, Oxford University Press 2018.

International Journal of Epidemiology, 47, 780–787.

[ix] Monahan, Emma Kahle, Yasmin Grewal-Kok, Gretchen Cusic, and Claire Anderson, “Economic and concrete supports: An evidence-based service for child welfare prevention”, Chapin Hall, April 2023

[x] Bulinger, Lindsey Rose, and Angela Boy, “association of Expanded Child Tax Credit Payments with Child Abuse and Neglect Emergency Department Visits, JAMA Network, February 16, 2023.

[xi] https://www.all4kids.org/news/blog/poverty-and-its-effects-on-children/

[xii] Marr, Chuck, Chye-Ching Huang, Arloc Sherman, and Brandon Debot, “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds”, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 1, 2015.

[xiii] Evans, Willian and Craig Garthwaite, “Giving Mom a Break”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, vol. 6, no. 2, May 2014 ; Anna, Aizer, Laura Stroud, and Stephen Buka, “Maternal Stress and Child Well-Being: Evidence from Siblings,” 2009, http://www4.gsb.columbia.edu/filemgr?file_id=6296; and

Adriana Camacho, “Stress and Birth Weight: Evidence from Terrorist Attacks,” American Economic Review, vol. 98,

- 2, pp. 511–515, May 2008.

[xiv] Ratcliffe, Caroline, “Child Poverty and Adult Success”, Urban Institute, September 2015

[xv] Bastian, Jacob, and Katherine Michelmore, “The Long-Term Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Children’s Education and Employment Outcomes”, SSRN, 2017

[xvi] Fisher, Jonathan, David Johnson, Timothy Smeeding, and Jeffrey P. Thompson, “Estimating the Marginal Propensity to Consume Using the Distributions of Income, Consumption, and Wealth.” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Research Department Working Papers No. 19-4, 2019. https://doi.org/10.29412/res.wp.2019.04

[xvii] Joint Economic Committee Democrats, “The Expanded Child Tax Credit Dramatically Reduced Child Poverty in 2021”, November 30, 2022.

[xviii] Schild, Jake; Sophie M. Collyer, Thesia Garner, Neeraj Kaushal, Jiwan Lee, Jane Waldfogel, and Christopher T. Wimer, “Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Household Spending: Estimates based on U.S. Consumer Expenditure Survey Data”, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 31412, June 2023